November 16, 2025

Updated: November 16, 2025

From Tor deanonymization to blockchain tracing and undercover stings, discover how police unmask criminals on the dark web in 2025 and why anonymity is no longer guaranteed.

Mohammed Khalil

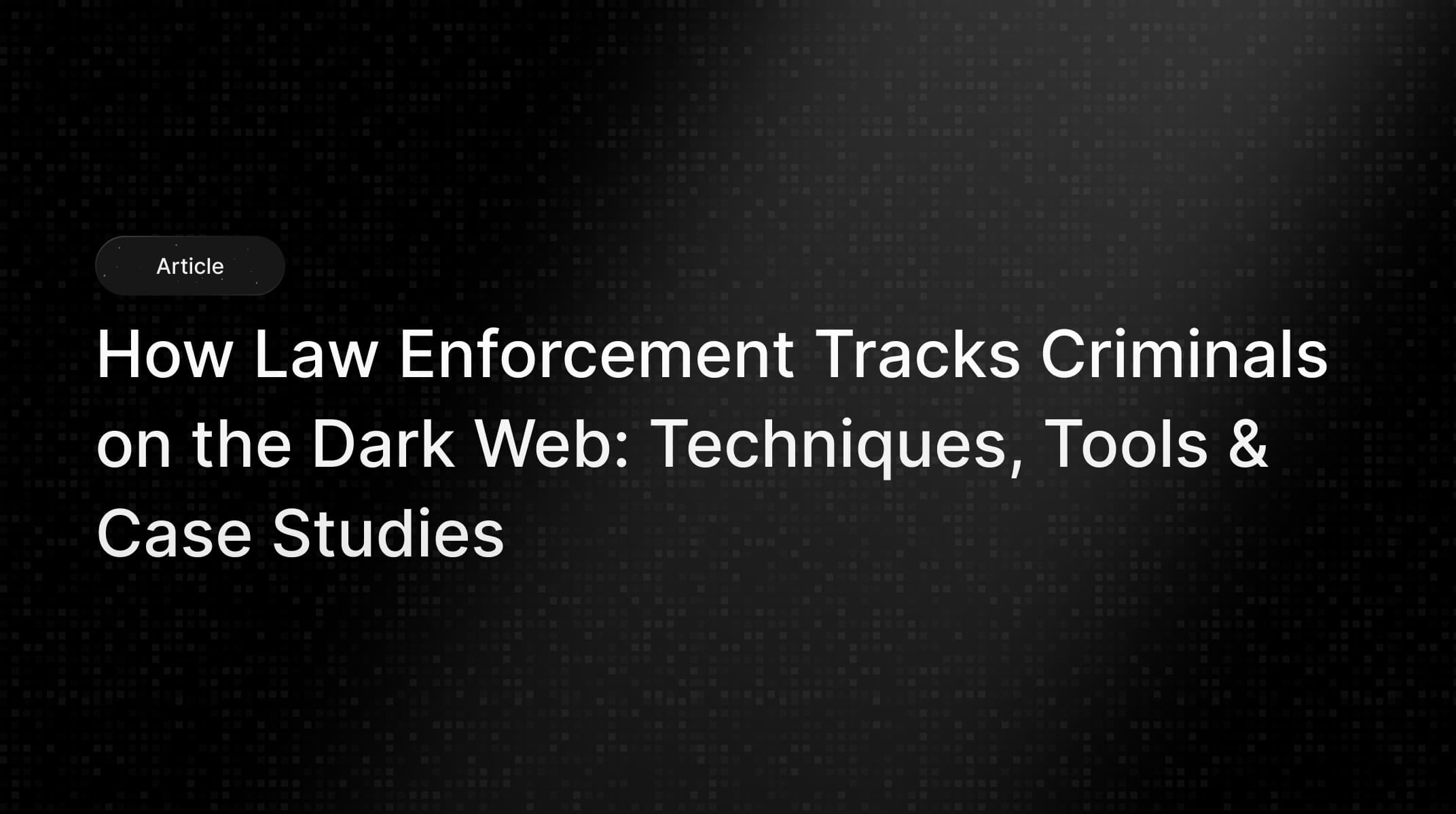

How do police catch criminals who hide behind Tor and secret online aliases? The answer: with a combination of technical wizardry, savvy investigative work, and yes sometimes the crooks’ own mistakes. Law enforcement tracks criminals on the dark web by exploiting any weakness in that shroud of anonymity. They’ve learned to crack encrypted networks, trace cryptocurrency transactions, and coordinate globally to hit suspects where they least expect it. In short, even on the dark web, you can run but increasingly you can’t hide.

The stakes are high. Here in 2025, the dark web isn’t just a playground for small time hackers it’s a bustling underworld marketplace for drugs, weapons, stolen data, and worse. One infamous hidden site was raking in an estimated $219 million a year in illegal sales. That kind of black market economy has put pressure on authorities worldwide to step up their game. Why this matters now: Dark web activity is growing, feeding real world crimes from opioid trafficking to cyberattacks. Tracking these shadowy criminals has become a top priority for agencies like the FBI, Europol, and Interpol. And as we’ll see, they’re getting smarter and more collaborative in their approach with some headline making successes to show for it.

Ready to dive in? This article breaks down how law enforcement actually investigates the dark web. We’ll cover what makes the dark web anonymous, the clever and sometimes brute force techniques police use to de anonymize Tor users, the high tech tools powering these investigations, and real case studies of dark web kingpins brought to justice. We’ll also discuss the legal tightrope that agencies walk when hacking into hidden services, and why international teamwork is the secret sauce behind many takedowns. By the end, you’ll see that even in the murky depths of the internet, criminals leave clues and law enforcement has learned how to follow them.

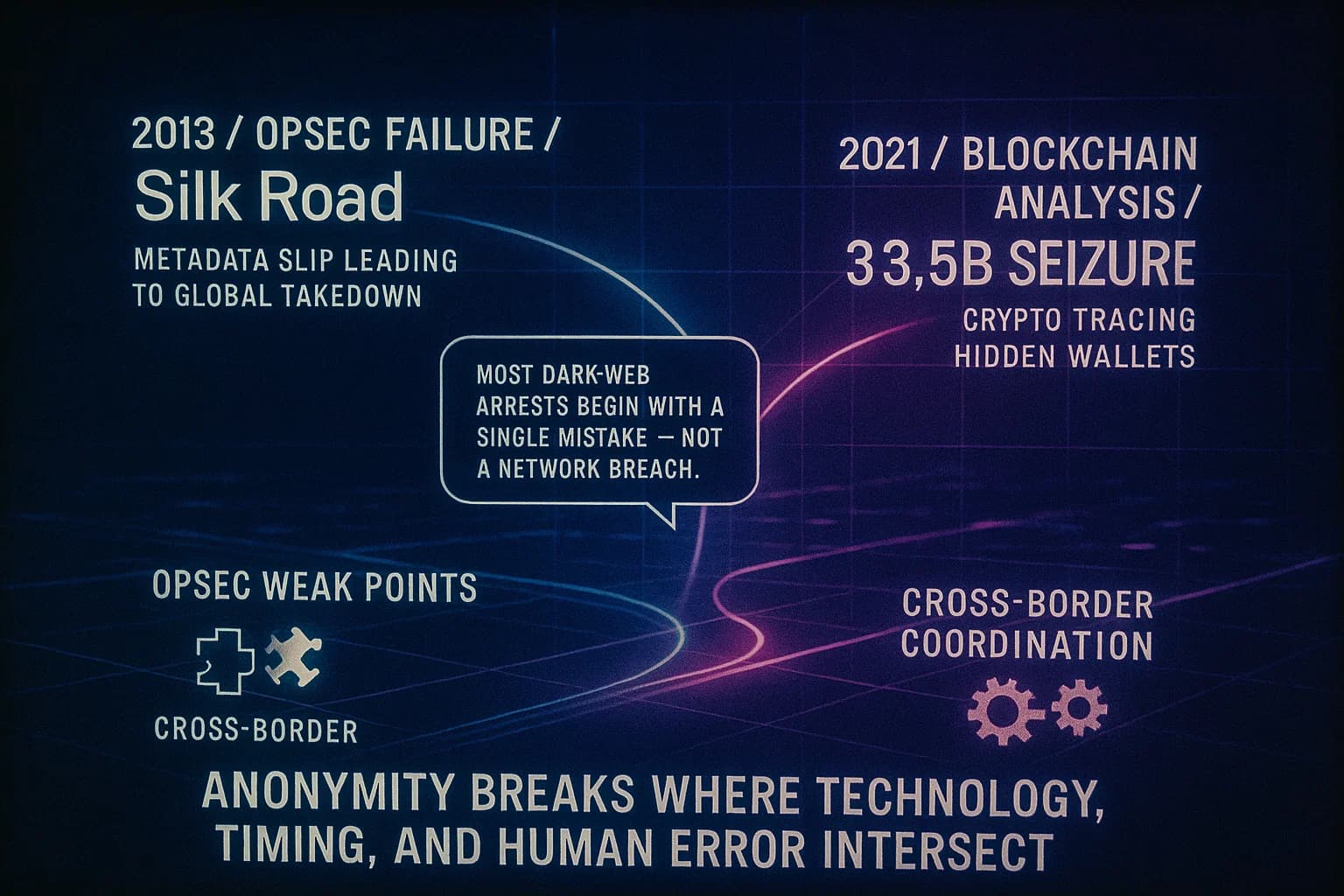

The dark web refers to the part of the internet that isn’t indexed by standard search engines and requires special software like the Tor browser to access. It’s often confused with the deep web, which simply means any non-public pages think private databases or emails but the dark web is a deliberate hidden realm. Websites on the dark web have masked IP addresses and use encryption to keep their operators and visitors anonymous. In practical terms, that means a criminal marketplace on the dark web can operate with a much lower risk of being discovered or shut down… at least initially check out our latest article about Deep Web vs Dark Web.

So why is the dark web hard to police? In a word: anonymity. Platforms like Tor The Onion Router bounce your internet traffic through layers of volunteer run servers around the world, wrapping it in encryption at every step. By the time your traffic reaches a website the exit node, no single server knows both who you are and what site you’re visiting. This onion-like routing makes tracing users or site hosts incredibly difficult. Similarly, dark web markets thrive on cryptocurrencies Bitcoin, Monero, etc., which let buyers and sellers pay each other without directly revealing identities. For law enforcement, it’s like chasing ghosts: no easy IP addresses to track, no credit card names to follow.

However, difficult doesn’t mean impossible. Over the past decade, police and federal agents have slowly but surely developed ways to shine a light on the dark web. They’ve found that while Tor and encryption provide strong anonymity, they are not foolproof. Every system has weaknesses and criminals often make mistakes that can break the anonymity cloak. In fact, many dark web busts happen because the perpetrators slipped up on their operational security OPSEC, not because of some magical decryption of Tor. Imagine a drug dealer using an untraceable site, but accidentally posting his real email address at some point yes, that’s a real example we’ll get to shortly.

To set the context, it’s worth noting that the dark web still accounts for only a fraction of all illicit activity online. Mainstream cybercrime like phishing or fraud often happens on the regular internet. But the dark web’s allure is growing especially for drug trade, child exploitation, and hacker for hire services. That means law enforcement can’t ignore it. Agencies have had to adapt their investigative playbook for this new domain. Traditional methods like subpoenaing an ISP for logs often hit a dead end when everything is encrypted or routed overseas. Thus, police forces now employ a mix of cyber expertise, undercover work, and partnerships with international and private organizations to tackle dark web cases. In the next sections, we’ll break down the core techniques and tools making a dent in that anonymity and show that even on the hidden internet, criminals leave traces that determined investigators can track.

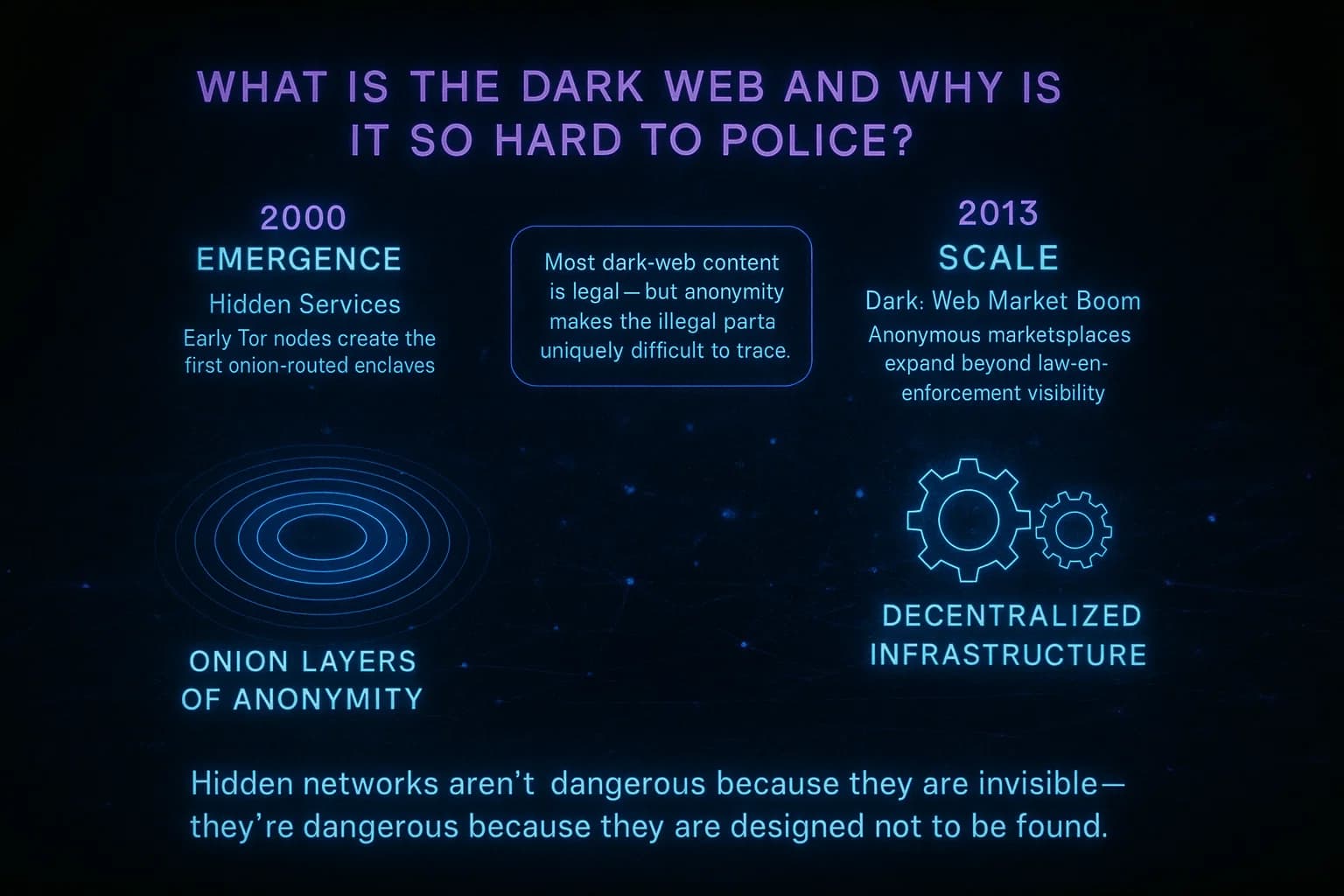

Unmasking a hidden criminal isn’t easy but it can be done. Law enforcement uses several technical and investigative techniques to deanonymize dark web users and gather evidence of their crimes. Here are the main strategies in play:

One high tech tactic is attacking the Tor network itself via traffic analysis. If investigators can monitor a large portion of Tor’s infrastructure, they can try to correlate the timing and volume of data going in and out of the network, effectively linking a user’s activity to a specific server or IP. In 2024, for example, a German task force pulled off a jaw dropping feat: they monitored numerous Tor servers relays for months and performed end to end timing analysis. By watching when encrypted traffic entered the Tor network and when it exited, and noting the sizes and timing of packets, they could statistically match some users to the dark web sites they were visiting. Essentially, if you control or spy on both the entry point and exit point of a Tor circuit, you can line up the clues and identify the source.

Why this matters: Tor is designed to be anonymous, but it’s not invincible. With enough resources and court orders, law enforcement can turn Tor’s strength the distributed network into a weakness by watching big chunks of it at once. In the German investigation, officers even got an ISP to reveal which customer was using a certain Tor entry node at a specific time. That led straight to an individual who was running a major illegal site on the dark web. This kind of timing correlation attack only works in certain scenarios it’s notably less effective if someone is only using Tor’s hidden services and not going out to the normal internet. But when it does work, it completely strips the anonymity from a target. The takeaway: Even Tor users can be unmasked if investigators are able to watch the network closely enough, as confirmed by the Tor Project’s own research into traffic correlation attacks.

What can police do when passive monitoring isn’t enough? Hack the hackers. In some cases, law enforcement obtains warrants to deploy malware against dark web users’ computers, a tactic bureaucratically termed a Network Investigative Technique NIT. This is essentially law enforcement using an exploit or malicious code to identify or snoop on suspects. One landmark example was the FBI’s operation Playpen in 2015. Playpen was a dark web child pornography site the FBI had secretly seized. Instead of immediately shutting it down, agents ran the site from an FBI facility for two weeks all while covertly delivering a malware payload to everyone who logged in. The malware took advantage of a hidden flaw in the Tor Browser which is a modified Firefox to force the user’s computer to send back its true IP address, MAC address, and other identifying data outside of the Tor network. Over a thousand users were unmasked this way, across the U.S. and Europe, leading to hundreds of arrests.

These NIT enabled watering hole hacks where anyone who visits a particular dark web site gets infected are controversial but effective. Essentially, the FBI turned the Playpen website into a honeypot, a trap that identified visitors by hacking them on the fly. This raised a flurry of legal challenges, as that single warrant was used to search thousands of computers around the world, pushing the limits of U.S. jurisdiction more on those legal issues later. Nonetheless, courts did convict many Playpen users thanks to this technique. Similar malware based stings have been used on other dark web forums as well. There’s even an anecdote from the Silk Road case though the FBI denied it that agents may have found the Silk Road server’s IP address by exploiting a misconfiguration in the site’s code basically hacking the hidden service to get it to reveal itself. Whether or not that particular story is true, it’s well documented that agencies have a playbook of browser exploits and hacking tools ready to go when traditional tracing fails.

The controversy: Government hacking blurs the line between defender and attacker. Privacy advocates like the ACLU argue that using malware this way can overstep warrants and endanger internet security if the exploits leak. In response, laws were updated e.g., Rule 41 of U.S. criminal procedure now explicitly allows judges to authorize remote hacking in certain cases to give these tactics a clearer legal footing. Still, judges and lawmakers continue to wrestle with how to balance catching criminals with not violating privacy for everyone else. From an investigator’s perspective, however, NITs are a game changer: They can reveal an anonymous user’s identity when no other clues exist. As one federal judge noted about such cases, When Tor or encryption hides suspects, a targeted exploit may be the only way to get a name on the suspect. In plain terms, sometimes law enforcement has to fight fire with fire using a hacker’s toolkit to beat the dark web’s anonymity.

Not all breakthroughs are high tech; often it’s a criminal’s own mistake that gives them away. OPSEC, short for operational security, refers to the practices that should keep an online criminal’s identity separate from their real life. But time and again, major dark web figures have been unmasked by bad OPSEC. Case in point: Ross Ulbricht, the founder of Silk Road, the first big dark web drug market, was ultimately caught because he reused usernames and left personal clues. Early on, Ulbricht went by the nickname altoid on a forum where he brazenly asked for tech help running a Tor hidden service and even dropped an email address containing his real name. That email was protected like a neon arrow pointing to him, once investigators found it. Agents also noticed someone with the username altoid had later posted on a Bitcoin forum offering jobs, listing the same email; and altoid was connected to the early promotion of Silk Road. By following this breadcrumb, they identified Ross Ulbricht.

Ulbricht made more slip ups: forensic analysis showed he logged into Silk Road from his home Wi Fi at least once, exposing an IP address near his apartment. He kept an incriminating diary and business plans on his personal laptop and cloud storage which, when seized, were gold mines of evidence. In 2013, police lured him to a public library and arrested him while he was logged in as Silk Road’s admin, effectively catching him red handed. Similarly, Alexandre Cazes, the Canadian behind the AlphaBay market, got comfortable and sloppy. He used his personal email to send out automated welcome messages to new AlphaBay users. Yes, unbelievably, the AlphaBay admin’s real name was right there in the onboarding email! That blunder gave investigators a concrete lead to trace him. Cazes also failed to completely hide his administrative activities on AlphaBay’s servers; once authorities had his name from the email, they could correlate it with other data and eventually pinpoint him in Bangkok. When he was arrested, Cazes’ laptop was unencrypted and logged in, revealing a treasure trove of files about AlphaBay’s operation and finances, even a document listing his many luxury cars and properties, titled AlphaBay Assets. Needless to say, that did not help his case.

Most dark web busts start with an OPSEC failure, not a fancy crypto crack. Investigators know this, so they actively scour for any link between an online alias and a real identity. They’ll comb forums, social media, leaks, and past posts to find if the suspect ever reused a username, email, or PGP key. In the words of one cybercrime agent, Give me one piece of re used personal info, and I can unravel the whole pseudonym. That might be an exaggeration, but as Ulbricht and Cazes learned, even a single reused email or sloppy login can bring down an empire. Modern dark web investigators often include OSINT open source intelligence specialists who do exactly this: gather every fragment of a suspect’s online trail. They’ll use techniques like linguistic analysis comparing writing styles and metadata analysis checking document properties or image GPS tags to connect the dots. The lesson for criminals not that we’re giving advice: If you mix your personal life with your secret dark web persona, odds are you’ll eventually get caught. And indeed, many of the biggest anonymous cybercriminals turned out to have made a dumb mistake that law enforcement pounced on.

The dark web may be digital, but sometimes age-old undercover tactics are the most effective. Law enforcement infiltrates closed forums, poses as criminals, and even runs illicit services as honeypots to catch participants. A dramatic example is the takedown of Hansa Market in 2017. Hansa was a popular dark web marketplace trading everything from drugs to hacked data. Dutch police managed to secretly seize control of Hansa’s servers hosted in another country without tipping off users. For about a month, the Dutch authorities operated Hansa in stealth mode. During this period, something big happened: the world’s largest dark market at the time, AlphaBay, was taken down by a separate FBI led operation. The result? Thousands of displaced AlphaBay sellers and buyers flocked to Hansa, looking for a new platform unaware it was already run by law enforcement. The Dutch police happily welcomed this influx and logged everything: user credentials, private messages, drop addresses for shipments, you name it. They even sprinkled some subtle watermarks in Hansa’s files to track anyone reusing the data elsewhere.

When the trap was finally revealed and Hansa shut down, authorities had amassed a goldmine of evidence. Europol, the EU’s police agency, said the operation yielded thousands of user identities that led to follow up investigations worldwide. It was like pulling a huge net out of the ocean, wriggling with caught fish. Undercover work also happens on a smaller scale agents pose on forums, build trust over time, and then either gather intel or execute stings like arranging a large drug deal, only to bust the dealer. It’s risky because if undercover identities are exposed, it can put agents in danger or at least burn the operation. Additionally, there are strict rules to prevent entrapment law enforcement can offer opportunities to commit crime, but they can’t induce someone to do something they weren’t already willing to do. In dark web cases, usually the criminals are plenty willing on their own; the challenge is getting insiders or access. We’ve seen forums where an undercover agent became an administrator with access to user info, or where police quietly run a fake vendor account to interact with buyers and trace shipments.

The Hansa playbook has become a template: coordinated strikes that herd criminals from one platform into a police controlled platform, yielding mass arrests. It demonstrated that patience and cunning can be more effective than just hitting a site with a seizure notice on day one. The dark web community was stunned by this tactic suddenly, no one knew which market might secretly be a police sting. Trust among criminals dropped to new lows which is exactly what law enforcement hoped for. This kind of undercover work requires immense coordination as we’ll discuss in the collaboration section, but it’s arguably one of the most impactful methods to date. The key point: Not all dark web investigations rely on cracking tech, some rely on tricking criminals. When done right, a well executed sting can unravel entire networks from the inside. As a result, many dark web marketplace users now operate under the paranoia that any big new site could be owned by the feds. And honestly, that fear isn’t unfounded because it’s happened before, and it will likely happen again.

In practice, investigators often mix and match these techniques. A case might start with OSINT hints from an OPSEC lapse, then transition to a subpoena or hack to get more info, and finish with an undercover buy or a traffic analysis confirmation. For example, an FBI agent described the AlphaBay investigation as using traditional gumshoe detective work plus sophisticated new cyber tools they traced bitcoins on the blockchain, subpoenaed an email provider once they had Cazes’s address, and coordinated a take down with Thai police. The overarching message is that no single method guarantees success, but if there’s a weak link in a criminal’s defenses, law enforcement will exploit it whether it’s a technical vulnerability or a human mistake. The dark web may promise anonymity, but as we move on to the tools section, you’ll see how technology has also given police new superpowers in chasing those who lurk in the shadows.

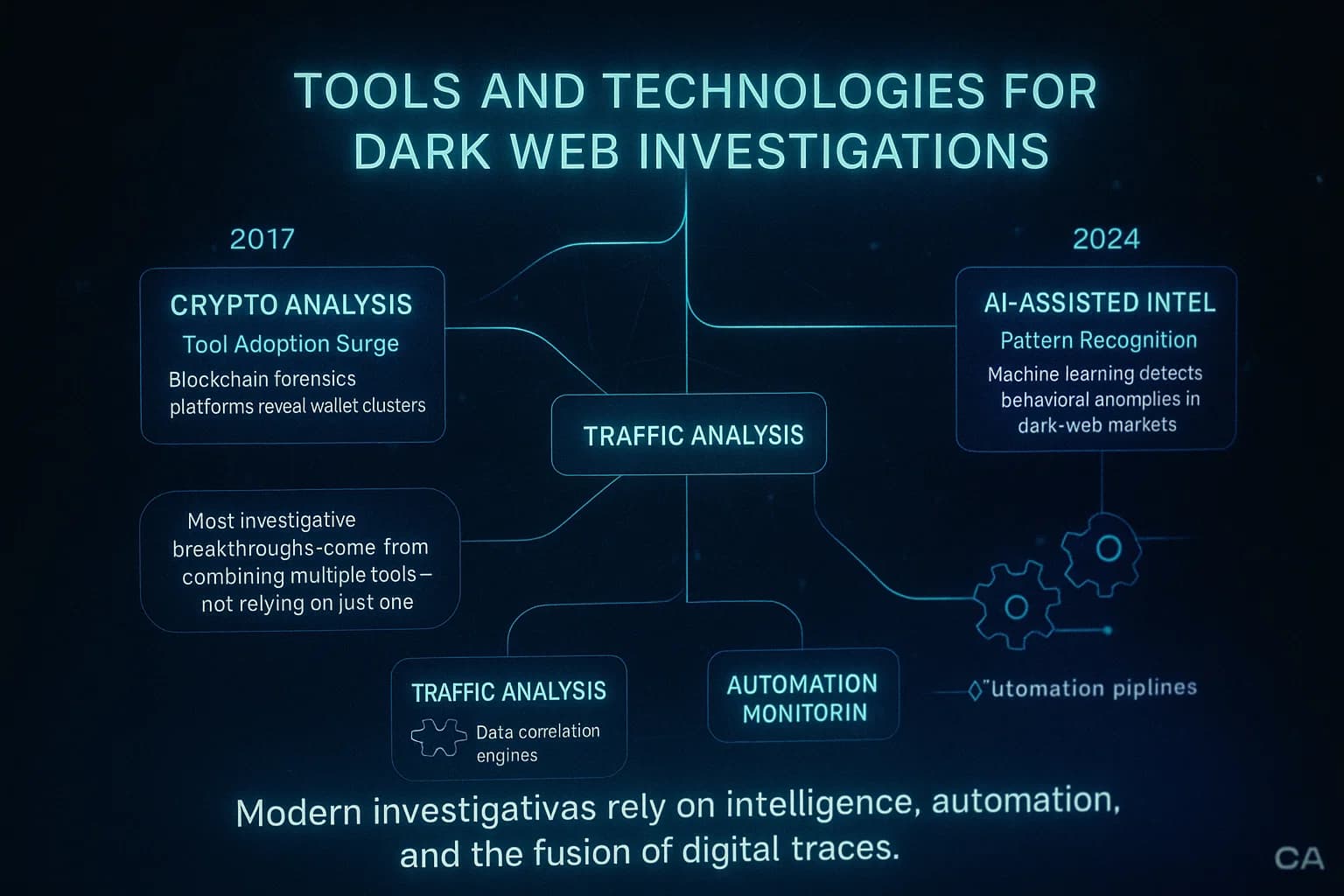

To track criminals in an anonymous realm, law enforcement has assembled a cutting edge toolbox. From blockchain forensics to web crawlers, these tools help turn the tables on dark web criminals. Below are key categories of technology and software that police and analysts use when investigating dark web activity:

Cryptocurrency is the lifeblood of dark web commerce but contrary to popular belief, Bitcoin isn’t truly untraceable. In fact, Bitcoin’s public ledger has become one of law enforcement’s best friends. Agencies use blockchain analysis platforms like Chainalysis, TRM Labs, Elliptic, and others to follow the money. These specialized tools can crunch the entire history of crypto transactions and flag patterns or known wallet addresses. For example, if Drug Dealer Dan’s dark web vendor account only accepts Bitcoin, investigators might extract the vendor’s Bitcoin address from the market via undercover buys or a site seizure and plug it into a tracing tool. The software will map out where Dan’s bitcoins have traveled, perhaps identifying that he cashed out to a particular cryptocurrency exchange. With a subpoena to that exchange or cooperation from a crypto analytics company, suddenly the supposedly anonymous Bitcoin leads to Dan’s real name and bank account.

One famous case demonstrating crypto tracing was the takedown of AlphaBay in 2017. Alphabay dealt heavily in Bitcoin and Monero. While Monero, a privacy coin, couldn't be traced, Bitcoin could and agents followed Bitcoin flows to locate AlphaBay’s servers and even tie some funds to Cazes, the administrator. Andy Greenberg’s book Tracers in the Dark details how IRS agent Tigran Gambaryan used Chainalysis tools to crack cases like AlphaBay and the Welcome to Video child exploitation site. In Welcome to Video, hundreds of users were arrested worldwide after blockchain forensics traced the Bitcoin payments they made for illegal videos. Investigators identified 337 suspects across 38 countries and rescued 23 children in that operation all by following the crypto money trail. Modern blockchain tools provide user-friendly visual graphs, cluster analysis linking many addresses to one entity, and even risk scores to highlight suspicious wallets. They have effectively turned Bitcoin’s transparency into a weapon against criminal users. One cybersecurity analyst put it this way: They could follow the money with even greater forensic power than in the traditional finance system. In fact, by 2025, the largest seizures of criminal funds in U.S. history have all been crypto related, thanks to these tracing capabilities.

Of course, criminals adapt many now use coins like Monero or mixers/tumblers to obscure their trails. But even those tactics have weaknesses. Analysts can sometimes de mix transactions with advanced heuristics, or catch criminals when they eventually convert coins to cash which usually involves a regulated exchange. The cat and mouse continues, but the big picture is clear: blockchain analysis has stripped away a layer of anonymity that dark web dealers once relied on. Law enforcement agencies today often have dedicated crypto tracing units or contracts with companies like Chainalysis for this purpose. What was once a niche skill is now mainstream in cyber investigations. And beyond just catching culprits, crypto tracing also lets authorities seize illicit profits e.g., millions in Bitcoin from darknet markets, hitting criminals where it hurts their wallets.

Navigating the dark web manually is dangerous and inefficient. That’s why specialized dark web intelligence platforms have emerged. These tools, offered by companies such as DarkOwl, Flashpoint, Recorded Future, Searchlight Cyber, and others, automatically crawl and index content from hidden services, marketplaces, forums, and paste sites. Think of them as Google for the dark web but private, secure, and geared for investigators. Law enforcement agencies can use these dark web search engines to input keywords like a username, an email, or Fentanyl and get results across many hidden sites at once. This saves time and also provides a layer of safety; investigators aren’t directly engaging with the criminal sites while searching.

For example, an agent might use a platform to find all instances of a certain bitcoin address or PGP key on the dark web. Or they could search for chatter about an upcoming crime. Some tools send alerts when new mentions pop up helpful for tracking emerging threats or new leaks of stolen data. A big advantage is evidence preservation: these services often archive snapshots of sites and messages. If a market goes offline suddenly either taken down or an admin exit scams, law enforcement isn’t left in the dark they might have archived data to continue investigations. In fact, one provider advertises that their archived dark web documents meet legal admissibility requirements, meaning the data can be used in court. This is crucial because collecting evidence directly from a live anonymous site can be challenged in court How do we know that screenshot is real?. But if it’s pulled from a trusted, timestamped repository, it’s more credible.

Dark web monitoring tools also assist in mapping criminal networks. After a bust, police can use them to find where else a certain alias operated. For instance, after the Hansa Market sting, Dutch police passed thousands of usernames to Europol. Agents could then search if those usernames appeared on other forums or markets, building out investigative leads. These platforms effectively turn the dark web inside out for investigators making the hidden world searchable and connectable. They can even help identify new marketplaces popping up or changes in criminal tactics e.g., more activity moving to encrypted messaging apps. It’s worth noting that not only federal agencies use these tools; local police and even commercial cybersecurity teams use them for things like detecting if stolen data from a breach is being sold online. In summary, what Google did for the open web, these dark web monitoring tools do for the dark web and they’ve become an indispensable part of the cybercrime fighting toolkit. Law enforcement no longer has to poke around blind on Tor; they have a search and alert system for the underworld.

When arrests are made or servers seized, the investigation shifts to good old fashioned digital forensics. This involves analyzing computers, phones, or servers to extract evidence like chat logs, account info, crypto wallet files, and so on. Standard forensic software such as EnCase, FTK, or Magnet AXIOM is used to image hard drives and comb through data. But in dark web cases, there are some special focuses:

In short, once physical control of hardware is obtained, traditional digital detective work takes over. The big difference in dark web cases is the heavy use of encryption meaning law enforcement might bring in specialists or outside experts to crack or access locked data. There’s also often a need for big data analysis: for example, analyzing a seized server’s database of tens of thousands of illegal transactions. Agencies use analytical software like IBM’s i2 Analyst’s Notebook or Palantir to visualize connections e.g., which buyer accounts bought from which vendor accounts, etc.. After the Hansa takedown, the Dutch police had mountains of data to sort through, correlating it with real world identities and other cases. That’s where these analytic tools help find needles in haystacks like if the same username was reused on a legal site or if a particular Bitcoin address appears in multiple contexts.

One more aspect: network forensics. If law enforcement was monitoring network traffic, say, at an ISP or running a compromised Tor node, they might gather packet captures. These can be analyzed with tools like Wireshark or custom DPI Deep Packet Inspection systems to look for patterns unique to Tor traffic or clues in unencrypted parts of the data. In the German Tor deanonymization case, for instance, they looked at packet sizes and timing to fingerprint Tor usage.

All these pieces, device forensics, network logs, crypto traces eventually get combined to build a narrative and evidence chain for prosecution. The mantra for investigators is follow the data, whether it’s on a hard drive, in the blockchain, or zipping through the internet. The tools of digital forensics might not be flashy, but they often provide the concrete evidence documents, chat logs, etc. that courts need to convict dark web offenders.

In some cases, law enforcement targets the infrastructure that supports dark web operations. This can mean hacking or seizing the actual servers that host darknet sites, or leveraging control of internet infrastructure to their advantage. A prominent example was Operation Onymous in 2014, where a coalition of agencies took down dozens of Tor hidden sites in one coordinated sweep. How they located so many hidden service servers is still partly a mystery some suspect a vulnerability in the Tor protocol or an error common to those sites was exploited. Others think an intelligence agency like the NSA lent a hand with its capabilities. Regardless, the operation showed that hidden services could be discovered and physically seized.

Another approach is targeting the hosting providers or administrators behind the scenes. There have been cases where law enforcement tricked or coerced a web host into cooperating. For instance, the Silk Road 2.0 investigation in 2014 hinted that the admin’s OPSEC slip logging in without Tor and some hosting provider compliance led agents to the server location. More recently, European authorities shut down a bulletproof hosting company called CyberBunker that was home to multiple darknet sites they literally raided an old NATO bunker turned data center in Germany. By seizing the servers, they got databases and user info in one go.

Controlling Tor nodes is another angle. Tor has entry guard, middle, and exit nodes. If police run some of these or gain access to them, they can potentially do the traffic correlation attacks we discussed earlier. There have been instances where researchers possibly state sponsored set up malicious Tor relays to see if they can catch identifying info. The Tor Project actively monitors for such rogue nodes, but some might slip through. In 2021, there were reports of a sustained Sybil attack on Tor where someone spun up thousands of new relays, possibly to deanonymize users speculation was that it could be law enforcement or a research outfit. While unconfirmed, it shows the cat and mouse where even the network itself can be attacked.

Law enforcement also employs sinkholing or takedown notices when applicable. For example, if a dark web site uses a clear net domain name for some reason rare, but a few have, they can seize the domain. More often, after they grab a server, they’ll display a seizure banner on the .onion site for shock value as seen with AlphaBay, Hansa, etc., where visitors suddenly saw an FBI/Europol notice. These banners serve a psychological purpose too to make criminals paranoid that their favorite market is actually a trap as indeed Hansa was.

And let’s not forget the low tech infrastructure attack: postal mail. Many dark web crimes like drug dealing still involve shipping physical goods. Agencies collaborate with postal services to intercept and controlled deliver packages. A lot of vendor busts happen when the dealer goes to pick up a shipment or when their deliveries are consistently flagged by sniffer dogs and surveillance. That’s more old school policing, but it connects to the digital side through undercover buys on markets.

To summarize, attacking the backbone of dark web operations be it the servers, the network nodes, or the delivery channels is a key prong of the strategy. These methods often require international assistance since servers could be anywhere and sometimes skirt the edge of legality hacking servers raises issues if done across borders without permission. But when successful, infrastructure attacks can bring down multiple sites at once Operation Onymous or completely compromise a market’s data Silk Road, AlphaBay. One DEA official said after AlphaBay’s takedown, We will use every tool we have to stop criminals from exploiting the dark net and they mean it, whether it’s a sophisticated blockchain trace or literally pulling servers out of a datacenter. In the end, dark web criminals rely on real world infrastructure, and that is something law enforcement can ultimately find and put hands on with enough effort and cooperation.

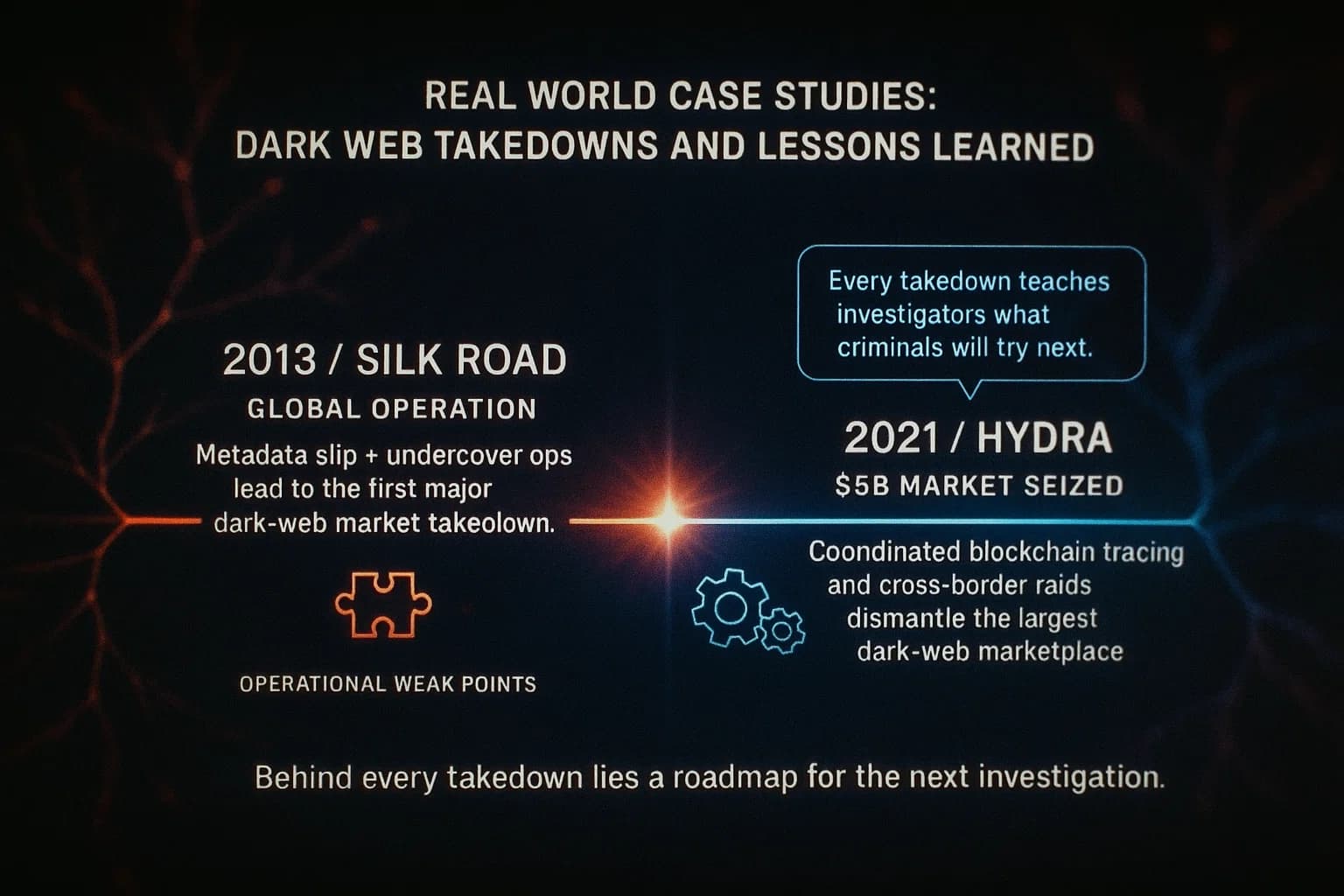

Nothing illustrates how law enforcement tracks dark web criminals better than the big cases that made headlines. Let’s look at a few high profile takedowns how they were achieved, and what each taught investigators and criminals:

| Dark Web Marketplace | Takedown Year | How They Were Caught | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Silk Road (Ross Ulbricht) | 2013 | Investigators found Ulbricht’s reused alias and personal email on forums. A leaky CAPTCHA exposed the server’s real IP, and he was traced via an IP address used at a public library. | Ulbricht (Dread Pirate Roberts) arrested in San Francisco with his laptop open; site shut down; life sentence. |

| AlphaBay (Alexandre Cazes) | 2017 | Blockchain tracing identified servers and linked funds to Cazes. He also used his personal email in welcome messages. | Cazes (Alpha02) arrested in Bangkok; servers seized; he died in custody; data led to many arrests. |

| Hansa Market | 2017 | Dutch police covertly operated the market for a month, logging activity; post‑AlphaBay surge gave extensive user data. | Hansa shut down; Europol investigations led to arrests across Europe and the U.S. |

Lessons Learned: Each takedown yields intelligence and sets precedents. Silk Road showed the importance of patience and OPSEC analysis. AlphaBay/Hansa showed the power of global coordination and following the money. Subsequent operations have continued to refine these methods. Law enforcement now often waits and watches, sometimes for years, to gather enough info and maybe let suspects incriminate themselves further. By the time the raid comes, they have a strong case. Another learning is the value of hitting the ecosystem at multiple points it’s not enough to arrest one guy; seizing servers, seizing criminal funds, and sharing intel to pursue accomplices are all part of the modern playbook.

From the criminal perspective, these cases instilled more paranoia. Many dark web market users started using better opsec like PGP for all messages, fragmentation of identity, etc., and market admins implemented new security features some markets went invite only or claimed to be decentralized. Yet, inevitably, people slip up and investigators adapt. The cat and mouse game continues, but clearly, the dark web is not the impenetrable safe haven it once seemed. As FBI Deputy Director Andrew McCabe said after AlphaBay was shut down, We will find and prosecute criminals wherever they operate, even on the dark web. The proof is in the arrests and the banners plastered on seized websites.

Chasing criminals in the dark web isn’t just a technical battle it’s a legal tightrope walk. Investigators often find themselves pushing the boundaries of search and surveillance laws, and dealing with thorny jurisdiction issues since these crimes span the globe. Here are the key legal and jurisdictional challenges law enforcement faces in dark web investigations:

The anonymity tools protecting dark web users also protect their legal rights, in a sense, by making traditional search warrants less effective. Normally, to search a computer, police present a warrant to a specific place/person. But what if they don’t know where the suspect is, because it’s just an IP hopping through Tor? That’s where the use of NITs network investigative techniques, essentially hacking, created new legal questions. In the Playpen case we discussed, the FBI obtained a warrant from a U.S. magistrate judge to deploy malware to any user worldwide who logged into that site. Defense attorneys argued this was basically a general warrant, something the Fourth Amendment usually forbids because it wasn’t narrowly tied to one person or place it was up to 158,000 computers across 120 countries! Several U.S. judges initially ruled evidence from that NIT was invalid because the magistrate exceeded her authority under the then current Federal Rule 41, a magistrate shouldn’t issue a warrant outside her district. To address this, in 2016 the rules were changed: now magistrates can authorize remote access to multiple computers in cases where the suspect’s location is hidden via technology. This legalized the kind of global hacking warrant used in Playpen but it’s still controversial.

Privacy advocates like the Electronic Frontier Foundation EFF and ACLU also raised alarms that government hacking, if not carefully restrained, could compromise innocent users’ security. For example, in the Playpen operation, the FBI did not initially reveal the technical details of the Firefox exploit it used. Organizations argued that keeping such exploits secret meant the FBI left a hole open that bad actors could also use since until it’s patched, everyone using that browser is at risk. In some cases, the FBI has dropped prosecutions rather than disclose the exploit in court, to avoid setting a precedent of forced disclosure. This is a tension: using cutting edge exploits helps catch bad guys, but it also means the government is stockpiling and using tools that undermine software security which could backfire if leaked or stolen. And indeed, there have been instances of law enforcement hacking tools getting out the NSA’s leaked exploits come to mind, though that’s intel agency, not police.

Then there’s encryption. Many suspects simply encrypt their devices or communications, posing a huge challenge. Some countries have laws compelling decryption the UK can charge someone for not giving up passwords, for instance, while others like the U.S. are still hashing out how that fits with the Fifth Amendment right against self incrimination. It remains a contentious issue in court whether forcing someone to reveal a password is constitutional. Typically, law enforcement tries alternative routes: spyware to capture the password, finding the password written down somewhere during a search, or using forensic tools to break weak encryption if possible. In high profile cases, police have also lobbied for backdoors in encryption something privacy experts strongly oppose. This debate is larger than just the dark web, but it certainly comes into play when an arrest leads to an unreadable hard drive full of potential evidence.

Lastly, undercover operations raise legal ethics questions like entrapment. Agencies have to be cautious: they can’t initiate illegal transactions that wouldn’t have happened otherwise. In the Hansa case, for example, Dutch police let the market run but presumably did not themselves start selling drugs they just observed and maybe moderated to keep things business as usual. If an undercover agent on a forum lures someone into committing a crime they weren’t actively looking to do, that could be thrown out as entrapment. So agencies train their undercover operators to let the suspects lead. In stings, they often give suspects chances to back out or show that the suspect was eager on their own. This way, if challenged in court, they can argue the person was predisposed to commit the crime.

In summary, law enforcement has had to get creative with warrants e.g., multi district hacking warrants, and navigate the minefield of privacy laws. The courts are gradually catching up: precedents are being set on what’s allowed. For instance, U.S. courts have largely upheld that deploying a NIT with a valid warrant is okay, and that if it collects only a limited set of data IP address, OS info, it’s not overly broad. But judges have also indicated that had the malware done more like searched files, they might rule differently. Each new tech they want to use, be it scraping a forum, impersonating a suspect online, or hacking a device often requires novel legal reasoning. It’s a balancing act: ensure evidence is admissible and rights aren’t violated, while still getting the job done against savvy criminals.

Because dark web crimes are borderless, jurisdiction is a nightmare. Who prosecutes whom, and under what laws, when a guy in Europe runs a site hosted in Asia selling to Americans? Typically, agencies go after suspects wherever they can get hands on them. But cooperation is key. If a suspect is in Country X that has no extradition treaty, they might escape consequences several Russian cybercriminals indicted by the U.S. remain at large in Russia, for instance. Law enforcement tries to coordinate international actions to avoid safe havens. The AlphaBay case highlighted how crucial this is: without Thai authorities willing to arrest Cazes locally, the whole operation could have crumbled. Similarly, the takedown of that CSAM network in 2025 by U.S., German, and Brazilian authorities required each country to act simultaneously arrest in Brazil, server seizures in Germany. They used formal mutual legal assistance treaties MLATs to share evidence and get warrants abroad, but also informal partnerships via Europol and Interpol to speed things up.

Jurisdiction extends to court as well: bringing evidence from a foreign country into your court can be tricky. It has to be obtained in a way that doesn’t violate that country’s laws or the terms of cooperation. If, say, German police secretly hack a server in a third country without permission, the evidence might be tainted or unusable, and it could cause diplomatic issues. Thus, the legality of cross border hacking is still largely uncharted. Some countries have started to allow it with conditions the updated Budapest Convention on cybercrime is moving that direction allowing law enforcement to directly preserve or collect data across borders in some scenarios. But usually, the safer route is to ask the other country’s police to do the operation. That’s why multinational operations involve synchronized warrants: each team operates on its home turf at the same agreed time.

Another challenge: presenting technical evidence in court. Prosecutors have to translate geek to English for judges and juries. When you have evidence like traffic analysis determined IP X was likely user Y, you need expert witnesses to explain that science in an understandable way and defend it under cross examination. Defense attorneys might argue that the methods are unproven or have error rates. For blockchain, prosecutors have to carefully show the chain of custody of digital evidence: how do we know that Bitcoin address belongs to the defendant? Often it’s by linking it to an exchange account in their name, etc. They also have to introduce things like dark web site data. If a site’s database is seized, the prosecution must authenticate it sometimes through the agent who seized it, other times through forensic analysts. They need to avoid hearsay issues for instance, chat logs where the defendant allegedly is writing under a pseudonym need linkage to him they usually use corroborating evidence like finding the same chat on his computer or the style matching, etc.. It can get complex.

Chain of custody is paramount: any gap and the defense will motion to suppress. This means from the moment digital evidence is collected, a server image, a hard drive, etc., every hand that touches it and every step of analysis must be documented. Interestingly, as mentioned, companies like DarkOwl brag that their archived dark web data holds up in court. In practice, an agent might testify that they used DarkOwl’s tool to capture the content of a site on a given date, and that it matches what was later found on the suspect’s computer, for example.

Then there’s the issue of attribution. Just because someone’s computer accessed a dark web site doesn’t automatically prove they did it intentionally, maybe malware did? maybe someone else in the house?. Prosecutors often stack evidence to eliminate alternative explanations. In Ulbricht’s trial, they had him logged in as admin in public, plus all the files on his laptop, plus posts linking to him an avalanche that removed doubt. In some cases, courts have accepted evidence that e.g. the accused’s laptop had the Tor browser installed and was the same machine that accessed the site, and nobody else had access to that machine as sufficient to attribute activity.

Cross border evidence can raise extra questions: if evidence was collected by foreign police under different legal standards, say, no warrant needed in their country for something, can it be used in a U.S. court? Generally yes, if U.S. agents weren’t involved in a way that bypasses U.S. law. It’s called the silver platter doctrine foreign evidence handed on a platter is admissible even if that country’s police don’t follow U.S. rules, as long as our agents didn’t direct them to break rules. But if cooperation is too close, defense might argue a joint venture existed and thus U.S. standards should apply.

Lastly, consider safe havens: Some criminals remain out of reach. The U.S. has indicted several Russian individuals for running dark web forums like Infraud or Hydra market admins, but because they’re in Russia which doesn’t extradite its citizens, they haven’t been arrested. Law enforcement tries to entice such figures to travel to neutral ground. There have been some captures that way e.g., a Russian Bitcoin launderer was nabbed in Greece while vacationing, because Greece had an extradition treaty. Still, it’s a waiting game. Essentially, law enforcement tracks these folks and if they slip up by leaving their safe haven, they’ll pounce. The frustration is evident: You can identify perpetrators with incredible accuracy thanks to the blockchain, but if they’re beyond the reach of Western law enforcement, they can still be beyond accountability, as one expert noted. This is why global cooperation is so vital one country’s unreachable suspect might be within another’s grasp.

In short, the legal landscape is complex. Each dark web case sets a bit more precedent on how to handle novel investigative methods in court. Internationally, efforts are underway to streamline cooperation like Europol’s joint task forces, or discussions about cross border data sharing in treaties. But it’s still often a case by case patchwork. Investigators not only have to be tech savvy, they need to coordinate closely with legal counsel to ensure their clever tactics don’t backfire legally. No one wants to spend two years deanonymizing a criminal, only for the evidence to get thrown out on a technicality. Thus, agencies have become more proactive in involving prosecutors early, obtaining innovative warrants explicitly covering what they plan to do, and documenting everything to withstand scrutiny. It’s not the Wild West; they know that to nail a conviction, they must dot the i’s and cross the t’s as tightly as they chase the clues.

When criminals operate without borders, law enforcement must do the same. The most successful dark web investigations have one thing in common: teamwork across agencies and countries. No single police department or agency, no matter how talented, can single handedly take down a global darknet marketplace that has servers in five countries and users in 100. Here’s how international collaboration supercharges dark web enforcement:

Major takedowns like AlphaBay were essentially joint operations on a Hollywood movie scale. In that case, the FBI and DEA led from the U.S., but they had parallel efforts with Europol, Dutch Police, Thai Police, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, UK’s NCA, etc.. They formed an informal task force where each brought something to the table the FBI had undercover buys and blockchain intel, Europol helped coordinate intel sharing, the Dutch were already working on Hansa which they folded into the plan, and the Thais were ready to move on Cazes. By striking together, they prevented suspects from fleeing or data from being moved.

Europol’s European Cybercrime Centre EC3 has been instrumental in facilitating such multi-country efforts. They host the Joint Cybercrime Action Taskforce J CAT, which is basically a permanent cyber task force in The Hague where liaison officers from numerous countries sit together, share leads, and plan operations. This direct communication cuts through the red tape of formal requests. For dark web cases, J CAT has coordinated sweeps like Operation Onymous and later Operation Silveraxe a 2019 action against counterfeit money vendors on the dark web. Interpol also plays a role globally, organizing meetings and connecting countries that might not usually work together.

Another form of joint operation is bilateral: e.g., U.S. Homeland Security might run a case jointly with Australian Federal Police if an Australian suspect is selling to Americans. They might detail agents to each other’s country or run mirror investigations that meet in the middle. We also see embed programs: FBI has legal attachés in many countries that grease the wheels for these partnerships, and conversely some European police have officers embedded in FBI or DEA units to share intel in real time.

The benefit of true joint ops is it allows for synchronized enforcement arresting multiple targets in different countries on the same day, so nobody has a chance to warn others or destroy evidence. A great example was the 2020 DisrupTor operation: it wasn’t one marketplace but a sweep of many vendors across the U.S. and Europe and some elsewhere. They timed 179 arrests in a span of days, hitting targets in six countries at once. That kind of coordination only happens through months of planning in multinational groups.

Beyond big stings, day to day sharing of intelligence is crucial. When one country seizes a dark web server or arrests a major player, the data collected is often handed over under controlled conditions to other affected countries. After AlphaBay’s fall, U.S. and Europol provided data to dozens of countries, enabling them to start their own cases. In the Hansa example, Dutch police gave Europol a list of all the Hansa user names, passwords, and address info they’d collected. Europol then distributed leads to various member states. This resulted in numerous follow on operations; for instance, in Germany, they arrested several big vendors identified from Hansa logs.

Interpol has a system called I-24/7 to share intelligence securely worldwide, which helps when non European countries need to exchange info on these cases. There are also ad hoc exchanges. If U.K. police identify an American suspect, they’ll usually pass that to U.S. authorities rather than pursue it themselves and vice versa. In fact, a lot of these cases start with a tip from one country to another: e.g., German police might notice a server for a drug forum is in their country and tip off the country where the admin is, or the FBI might decrypt a market’s private messages and find lots of Aussie customers’ addresses and send those to Australian police for local action.

One interesting collaborative intel initiative is the National Cyber Forensics & Training Alliance NCFTA, a nonprofit that includes law enforcement and industry. It’s U.S. centric but has international reach and focuses on things like sharing info on threats including dark web activities. It’s behind the scenes, but such alliances allow for intel to flow from private companies, say, a bank sees a bunch of stolen credit cards on a dark web site and tells NCFTA, which passes to the Secret Service and foreign partners.

The key here is speed and trust. The faster and more freely intel flows, the quicker law enforcement can act. That’s why establishing personal relationships via task forces is valuable investigators often say, I have my counterpart in X country on WhatsApp, we can coordinate in minutes rather than formal letters taking weeks. Of course, when it comes time for legal action searches, arrests, they still formalize via requests and joint plans. But having that initial sharing means everyone’s on the same page and evidence can be preserved in time.

Not every country has the expertise or tools to tackle dark web cases. International bodies work to raise the game globally. For instance, the UNODC UN Office on Drugs and Crime has programs to train developing countries’ cyber units. Interpol frequently conducts training sessions on cryptocurrency tracing and dark web investigations for police from various nations particularly in Asia, Africa where this might be newer. The idea is to ensure that when a global case comes knocking, those countries can participate effectively rather than be the weak link.

Europol’s EC3 and the FBI have also shared tools or provided on site support. Europol might send a mobile forensics lab to assist a country in extracting data from seized servers, etc. We saw this in some child exploitation dark web cases where a server might be in a country with limited capabilities Europol stepped in with technical know-how to get the data off it in a forensically sound manner.

Public private partnership is another cornerstone. A lot of the tools we talked about Chainalysis, TRM, DarkOwl are commercial. Law enforcement often contracts or partners with these companies. In the 2025 CSAM network case, TRM Labs openly took part and provided on chain analysis to identify the suspect. That’s a private company actively supporting an investigation. Similarly, Chainalysis has analysts that sometimes work directly with agencies on big cases, kind of like a consulting role. Crypto exchanges and tech companies also cooperate for example, when law enforcement traces crypto to an exchange, they rely on the exchange’s compliance team to quickly provide the KYC info. Many major exchanges are on board and have hotlines to law enforcement for urgent requests especially if it’s something like child exploitation or terrorism.

Shipping companies, financial institutions, cybersecurity firms all have roles. Case in point: UPS and FedEx security teams often work with postal inspectors to flag suspicious packages that might be dark web drug orders. Another example: banks might alert if a client receives numerous money orders from known crypto cash out points since some criminals cash out by buying things like prepaid cards or money orders. Everyone has a piece of the puzzle, and the best investigations integrate those pieces.

On the flip side, the dark web has given rise to less official collaborations: some white hat hackers or researchers have occasionally provided tips or vulnerabilities to law enforcement. There have been instances of independent researchers infiltrating a forum and then tipping off police. While law enforcement has to verify and do their own lawful collection, these tips can jumpstart a case.

All in all, global collaboration is the only way to keep up with global crime. The successes of recent years, the big market takedowns and the sweeping arrests would have been impossible without it. It’s telling that press releases often list a dozen agencies from as many countries, all sharing credit. As Europol’s director put it after AlphaBay/Hansa, The global law enforcement community is tighter than the criminals realize, and together we’re hitting them at every level. The dark web exposes the jurisdictional cracks in our world, but through collaboration, police are patching those cracks. A coordinated investigation in 2025 even managed to dismantle a darknet child abuse ring across three continents, explicitly citing that public private partnerships and international coordination enabled authorities to overcome numerous technical and jurisdictional challenges. In other words, by sharing expertise and trusting each other, the good guys are making the dark web a lot smaller for the bad guys.

The cat and mouse game between law enforcement and dark web criminals is well underway and it’s clear the cat is getting smarter. Tracking criminals on the dark web requires a fusion of technical prowess, global cooperation, and yes, occasionally a stroke of luck. In 2025, agencies have shown that anonymity tools like Tor and Bitcoin are not impenetrable walls but rather hurdles that can be overcome with the right strategy. We’ve seen how traffic analysis can unmask users, how blockchain forensics can follow dirty money, and how even the most careful criminals can be tripped up by a human mistake. Each big takedown from Silk Road to AlphaBay has reinforced that message: you might hide for a while, but if you’re a high value target, odds are the law, possibly laws, across countries will catch up.

For the public and businesses, these developments are a reminder that the dark web isn’t some mythical safe zone for criminals. Law enforcement has adapted, and many dark web perpetrators are being brought to justice. However, the flip side is that criminals also adapt using better encryption, shifting to new platforms, or operating from jurisdictions where they feel safe. It’s an ongoing cycle of innovation on both sides. The legal system is gradually adapting too, finding ways to accommodate new investigative techniques while trying to preserve civil liberties. It’s a delicate balance nobody wants a world where police hacking becomes overzealous, but at the same time, society demands action against egregious crimes hiding behind Tor.

From a purely technical viewpoint, what stands out is the importance of holistic investigation. There’s rarely a single magic button to reveal a dark web user. Instead, it’s layered work: follow the money, follow the metadata, follow the behavior, and coordinate across agencies to assemble the puzzle. In a way, these investigations have made law enforcement more collaborative and tech savvy than ever before. Agencies that never used to talk to each other now routinely sync up on operations. Cyber units that were once small adjuncts have become central to major crime investigations.

As we move forward, new challenges will emerge the rise of decentralized marketplaces, increased use of end to end encrypted messaging for deals, or criminals leveraging AI to evade detection. But the cat isn’t sleeping; law enforcement is embracing new technologies too AI for pattern recognition in large data sets, for example. The dark web may never be fully tamed, but it’s no longer the free for all it was a decade ago.

Ready to strengthen your defenses? The threats of 2025 demand more than just awareness; they require readiness. If you’re looking to validate your security posture, identify hidden risks, or build a resilient defense strategy, DeepStrike is here to help. Our team of practitioners provides clear, actionable guidance to protect your business. Explore our Penetration Testing Services to see how we can uncover vulnerabilities before attackers do. Drop us a line we’re always ready to dive in and bolster your defenses against even the stealthiest threats.

Mohammed Khalil is a Cybersecurity Architect at DeepStrike, specializing in advanced penetration testing and offensive security operations. With certifications including CISSP, OSCP, and OSWE, he has led numerous red team engagements for Fortune 500 companies, focusing on cloud security, application vulnerabilities, and adversary emulation. His work involves dissecting complex attack chains and developing resilient defense strategies for clients in the finance, healthcare, and technology sectors. Mohammed’s hands on experience in both attacking and defending systems gives him a unique perspective on emerging cyber threats including those lurking on the dark web and how organizations can stay one step ahead

Yes, under the right circumstances. The dark web via Tor is designed to anonymize users, but law enforcement can track people if they make mistakes or if investigators use advanced techniques. Police have de-anonymized users through traffic analysis watching Tor network patterns, deploying malware to reveal identities as in the Playpen case, tracing cryptocurrency transactions to real world accounts, or simply catching an OPSEC slip up like reusing a real email or address. While casual browsing of the dark web might not get you tracked, if you engage in illegal activity, you may draw attention. There have been multiple cases of dark web users being identified and arrested, proving that Tor isn’t a guarantee of impunity. In short: You can be tracked on the dark web if law enforcement has the resources and reasons to target you.

Many arrests happen because the person messed up their anonymity rather than Tor failing on its own. Common ways people get caught include: using the same username or password on the dark web as elsewhere, posting a personal email or identifiable info by accident, not using Tor 100% of the time even one login from a real IP can give you away, or leaving digital traces on their computer that police find during a raid. Additionally, law enforcement might catch someone through undercover buys ordering illegal goods to an address or by tracing crypto payments when the person cashes out. There have also been technical deanonymization successes for instance, a few years ago, researchers aided police in Germany to identify users by correlating Tor traffic timing. But more often, it’s human error or good investigative work like seizing a server and finding user logs that nails the suspect.

Generally, Tor is very hard to trace by design it was built to protect anonymity. Law enforcement cannot simply see through Tor encryption. However, they have identified Tor users by attacking the network in specific ways. One method is operating or monitoring enough Tor relays to perform a traffic correlation attack matching the timing of someone’s entry and exit traffic. This requires significant resources and isn’t always reliable, but it has worked in certain cases. Another method is targeting vulnerabilities in the Tor browser or protocols if the browser is out of date or misconfigured like Silk Road’s CAPTCHA leak, it can expose the IP address. Also, some users mistakenly access non onion sites while using Tor, potentially leaking identifying info some clearnet sites block Tor or log requests. In short, police can’t decrypt Tor traffic at will, but through network level surveillance or browser exploits, they have occasionally unmasked users. Other anonymity networks I2P, for example, have seen even less law enforcement attention, but if they grew in criminal use, similar principles would apply. As a rule: if an investigation targets someone strongly, agencies will try every trick to break through Tor and they have a few tricks up their sleeve.

Investigators use blockchain analysis tools to trace crypto. Cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin record every transaction on a public ledger. Specialized software can cluster addresses and track the flow of coins from one wallet to another. When a dark web vendor gets paid, those bitcoins might move through several addresses, but eventually the vendor may send them to an exchange to convert to cash or to a wallet that can be linked to them. Law enforcement often works with blockchain analytics firms like Chainalysis or TRM Labs to identify patterns for example, recognizing a deposit into an exchange’s known wallet. Then they send a legal request to that exchange for the account holder’s info. That’s how many dark web crypto cases crack open the moment the anonymous crypto touches the regulated financial system, it gains an identity. Even if criminals use mixers or tumblers to obscure the trail, advanced analytics can sometimes de-mix or at least follow portions of the funds and if any output eventually hits a known entity, that’s a lead. In one case, the Welcome to Video child porn site, investigators traced bitcoin payments from hundreds of users and got their names from exchanges, leading to multiple arrests worldwide. It’s worth noting that privacy coins like Monero are much harder to trace by design, their ledger obfuscates sender/receiver amounts, and law enforcement usually can’t follow those directly. But many dark web users still use Bitcoin, and Bitcoin tells a story if you know how to read it.

They have a whole arsenal of tools, both technical and investigative. On the technical side:

In addition to software, law enforcement uses techniques like controlled deliveries to link online orders to physical recipients, undercover buys, and traditional surveillance on suspects following a person, monitoring their phone metadata, etc., once they have a lead. So it’s a mix of high tech and classic policing. And of course, international information sharing systems like Europol’s SIENA network could be considered a tool that helps coordinate these complex cases.

Simply accessing the dark web is not illegal in most jurisdictions, including the U.S. and European countries. The Tor browser is legal and even funded partly by U.S. government grants! Plenty of legitimate uses exist journalists, activists, or just privacy conscious folks use Tor to protect their communications. There are also legal sites on the dark web for example, some news organizations have secure drop sites for whistleblowers. Law enforcement isn’t interested in people who just browse or poke around out of curiosity. They become interested when you engage in or facilitate criminal activity buying drugs, hiring hackers, trading illegal content, etc.. That said, stumbling around the dark web can be risky. You might encounter disturbing content or scams. Also, note that while using Tor is legal, doing so might draw a bit of extra scrutiny if, say, your workplace or school monitors network traffic they might wonder why you’re using Tor. But as far as the police are concerned, you won’t get in trouble just for using the dark web. It’s the what you do there that matters. If you do nothing illegal, law enforcement has no reason to track you. A tip: if you ever were questioned, simply explain your legitimate purpose e.g., academic research, curiosity, etc.. In many cybercrime cases, defendants incriminated themselves through their actions, not merely their presence on the network.

Stay secure with DeepStrike penetration testing services. Reach out for a quote or customized technical proposal today

Contact Us