Updated: November 1, 2025

Homoglyph attacks exploit look-alike Unicode characters to spoof domains, trick users, and bypass filters. Learn how they work, see real examples, and discover proven defenses.

Mohammed Khalil

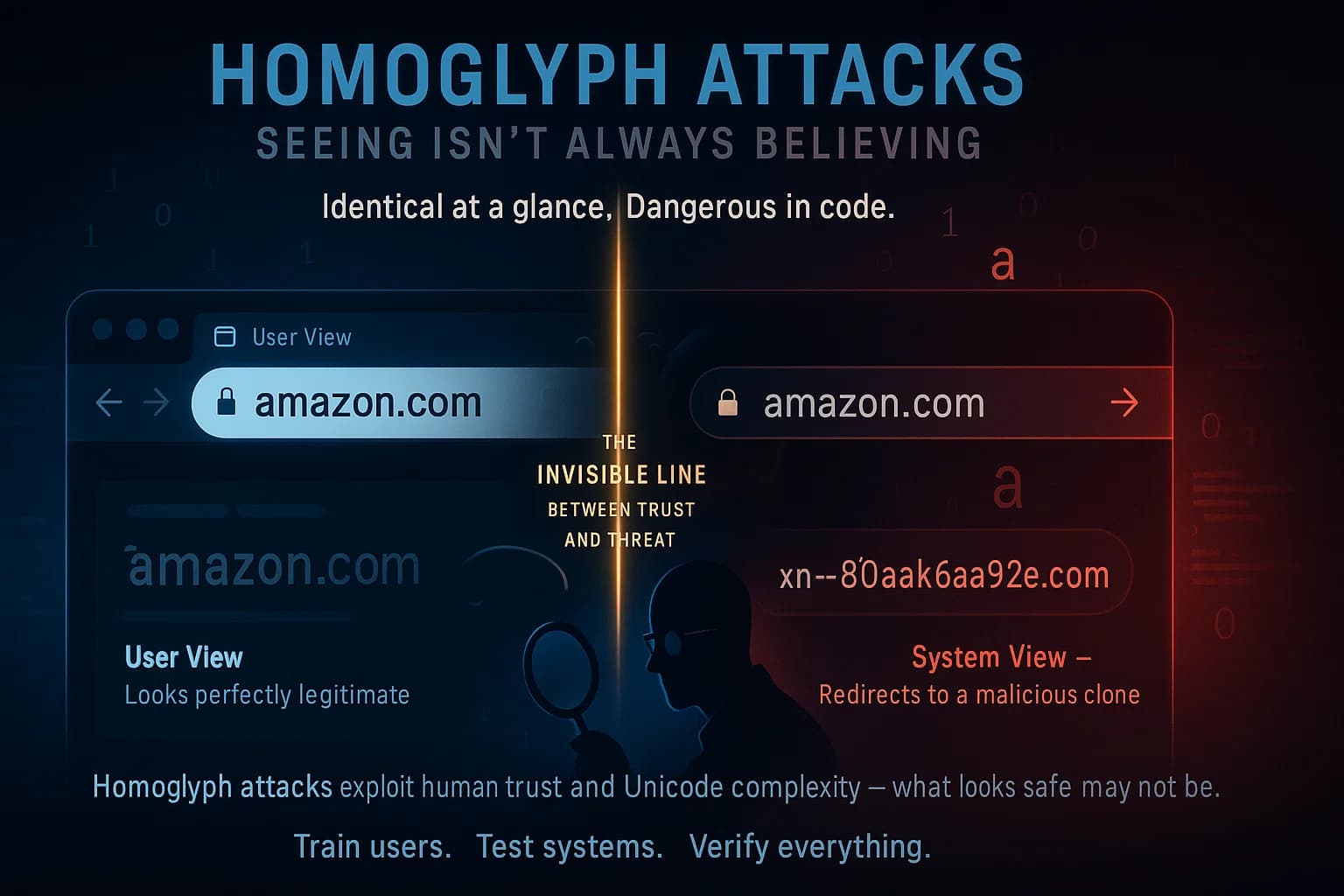

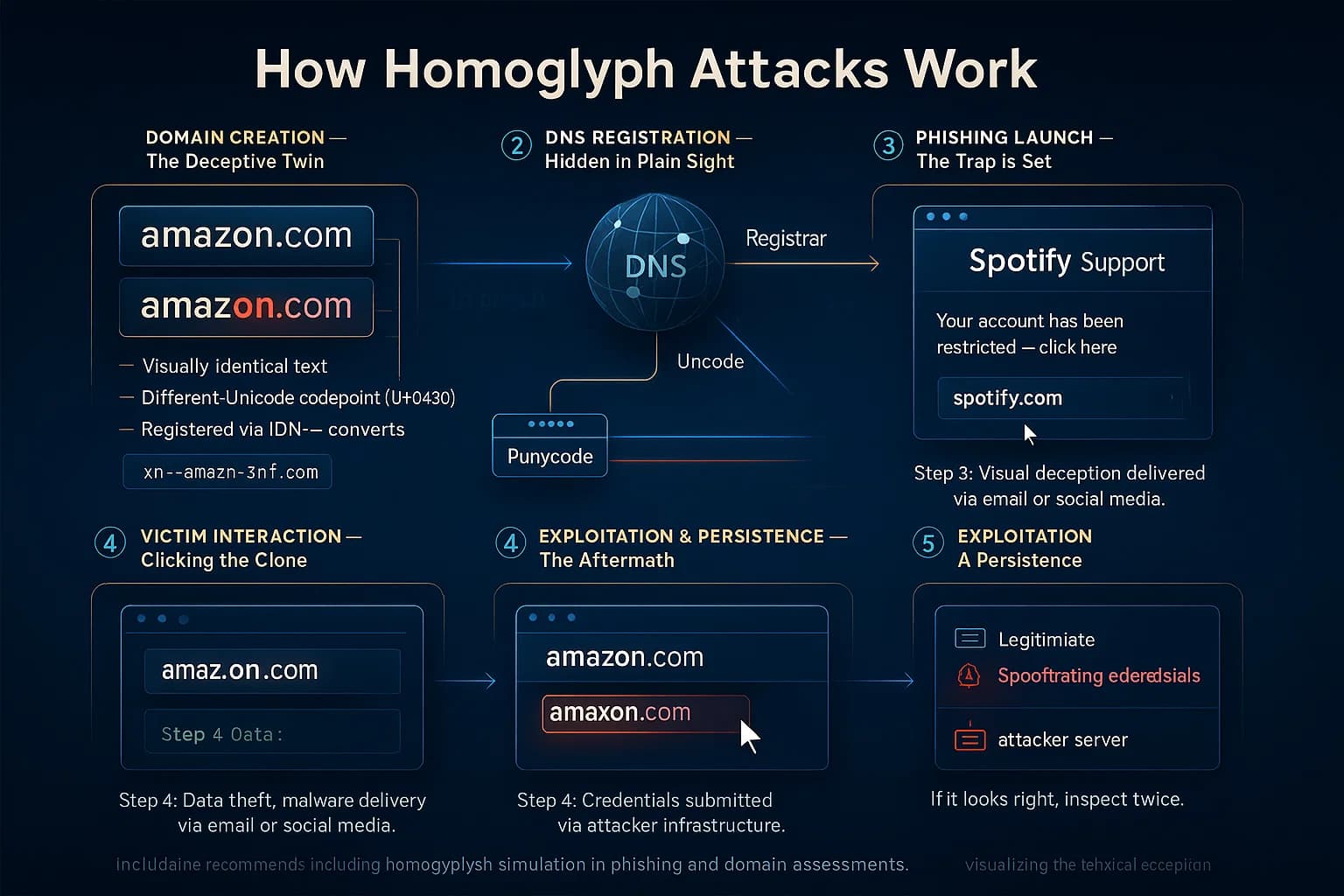

A homoglyph attack is a form of visual spoofing where attackers replace letters in a name or URL with nearly identical characters from another alphabet. In practice, a user may click a link that looks like “amazon.com” but contains a Greek ο or Cyrillic а in place of a Latin letter. The browser or email client shows a familiar string, but the link points to a different domain. This exploits how Unicode works: many alphabets have characters (glyphs) that are confusable. For example, Unicode small Cyrillic о (U+043E) is indistinguishable from Latin o (U+006F) on most screens. When IDN (Internationalized Domain Name) support is used, these spoof domains become valid in DNS, meaning “аррӏе.com” all Cyrillic letters can resolve independently from “apple.com”.

Penetration testing often includes social engineering and domain reconnaissance. As part of a phishing or red-team test, attackers may register lookalike domains to see if users or systems are fooled. For background on pentesting, see What is Penetration Testing? for how these assessments work. In a homoglyph test, a pen tester might spoof a login URL or sender address with visually deceptive characters. This exploits the fact that humans and simple filters misinterpret the characters. In short: homograph (homoglyph) attacks hide malicious domains in plain sight.

Homoglyph attacks rely on Unicode’s vast character set. Attackers mix scripts (Latin, Cyrillic, Greek, etc.) or use lookalike symbols so the text appears unchanged. For instance, Google’s documentation notes “Latin ‘a’ looks a lot like Cyrillic ‘а’”, so an attacker could register xn--80ak6aa92e.com (which renders as “ebаy.com” with Cyrillic а), a perfect knock-off of “ebay.com”. The browser may display it as “ebay.com” or at least not raise alarm, but it leads elsewhere.

Common Attack Scenarios:

Attackers exploit visual confusion: to a human, “citibank.com” with a Cyrillic с looks identical, so victims may hand over credentials, not realizing they’re on an imposter site. Automated systems can also be fooled: filters that scan for “paypal.com” won’t catch “paypal.com” (Latin vs Greek alpha). This makes homoglyphs a powerful tool to evade defenses and impersonate trusted brands.

| Attack Type | Method | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Homoglyph (Homograph) | Swap characters with visually similar Unicode glyphs. Relies on deception, not user error. | goоgle.com (Cyrillic о for Latin o); “Airplаnes R Us” (with Cyrillic а). |

| Typosquatting | Register common misspellings or typos of a known domain. Relies on user mistake. | gooogle.com (extra o), gogle.com (missing o). |

A typosquatting victim simply mistypes a URL, whereas a homoglyph attack actively tricks the user with what appears correct. In fact, typosquatting depends on user input errors, while homograph attacks work even when links are clicked. As the DarkOwl CSA blog explains, homoglyph fakes are created using lookalike symbols (e.g. using “0” for “O”), whereas typosquatting is a straightforward spelling error.

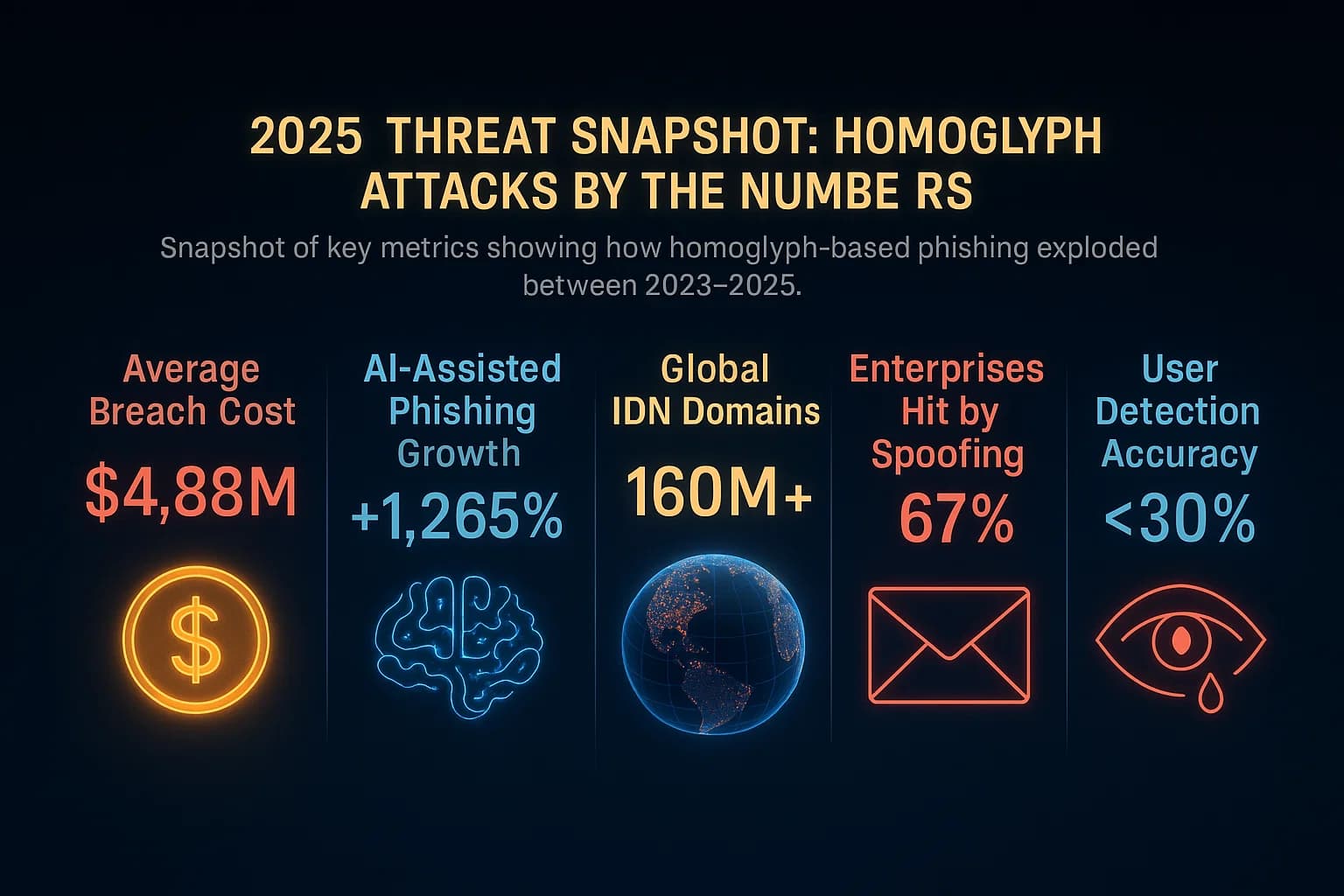

In today’s threat landscape, homoglyph attacks amplify phishing and social engineering risks. Phishing remains the top attack vector DeepStrike’s 2025 report highlights average breach costs of $4.88M for phishing-based incidents and $10.22M in the U.S. on average. Homoglyph spoofing is a favored tactic for threat actors, from nation-states to cybercriminal rings, because it can slip past email filters and trick even security-conscious users. With AI-driven phishing on the rise up 1,265% year-over-year, these deceptive domains are more dangerous than ever.

Moreover, as internationalized domain name IDNs proliferate globally, the attack surface grows. Non-ASCII character support means millions more possible lookalikes exist. Browsers like Chrome and Firefox have had to tighten their IDN policies; for example, Chrome now shows punycode for mixed-script domains to warn users. Still, in email clients or social networks, homoglyphs often render as normal text. This tactic has led to high-profile scams: from Google Drive phishing to business email compromise BEC schemes. For organizations, any account takeover or data theft facilitated by a homoglyph site can trigger expensive breaches and regulatory fines. In short, proactive testing and defense against homograph attacks is critical to protect brand and data integrity.

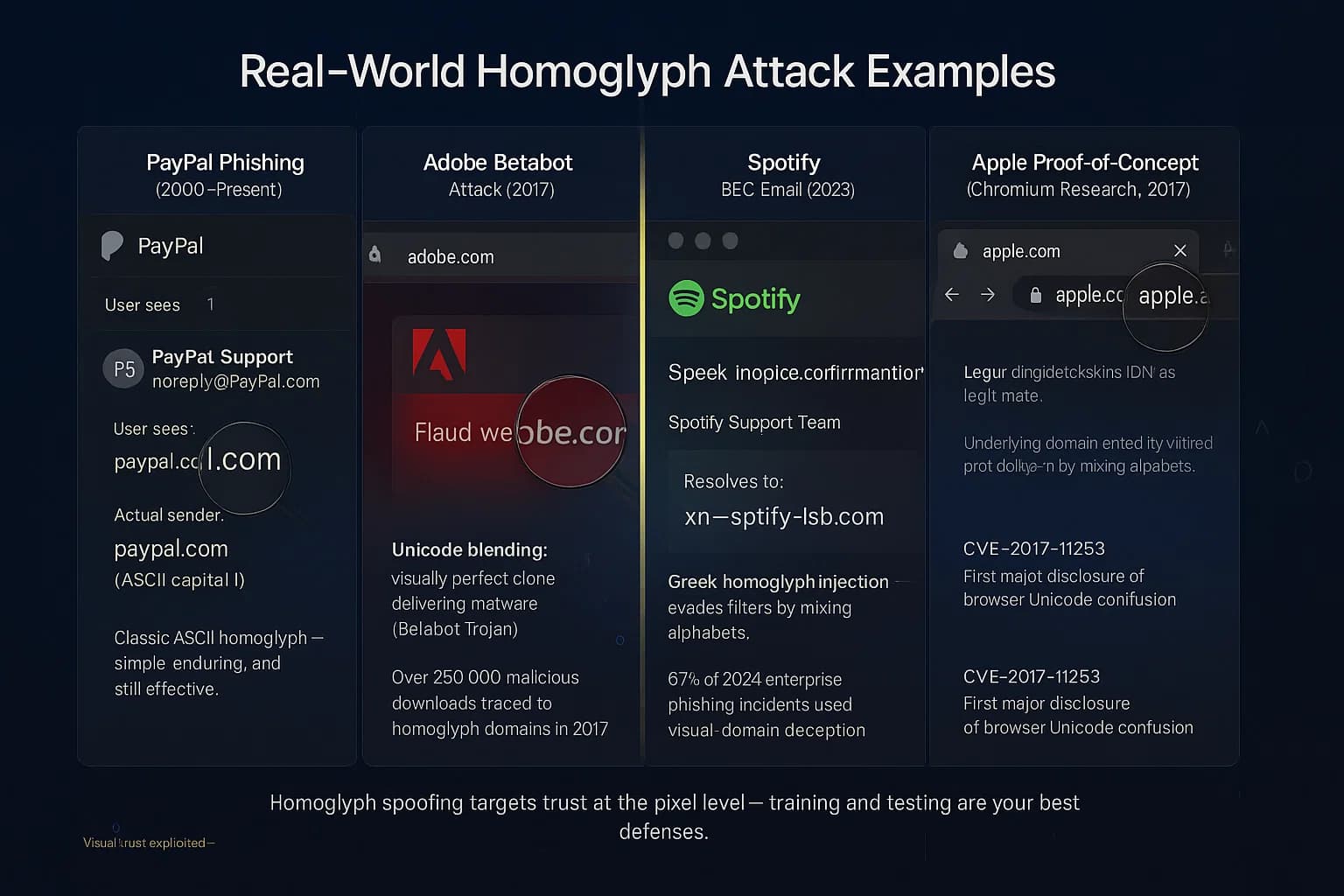

These incidents highlight that even savvy users and automated defenses can be fooled by homoglyphs. They also show a common pattern: the top-level domain (TLD) remained the same e.g. “.com”, but the letters themselves came from another alphabet, blending seamlessly into the interface.

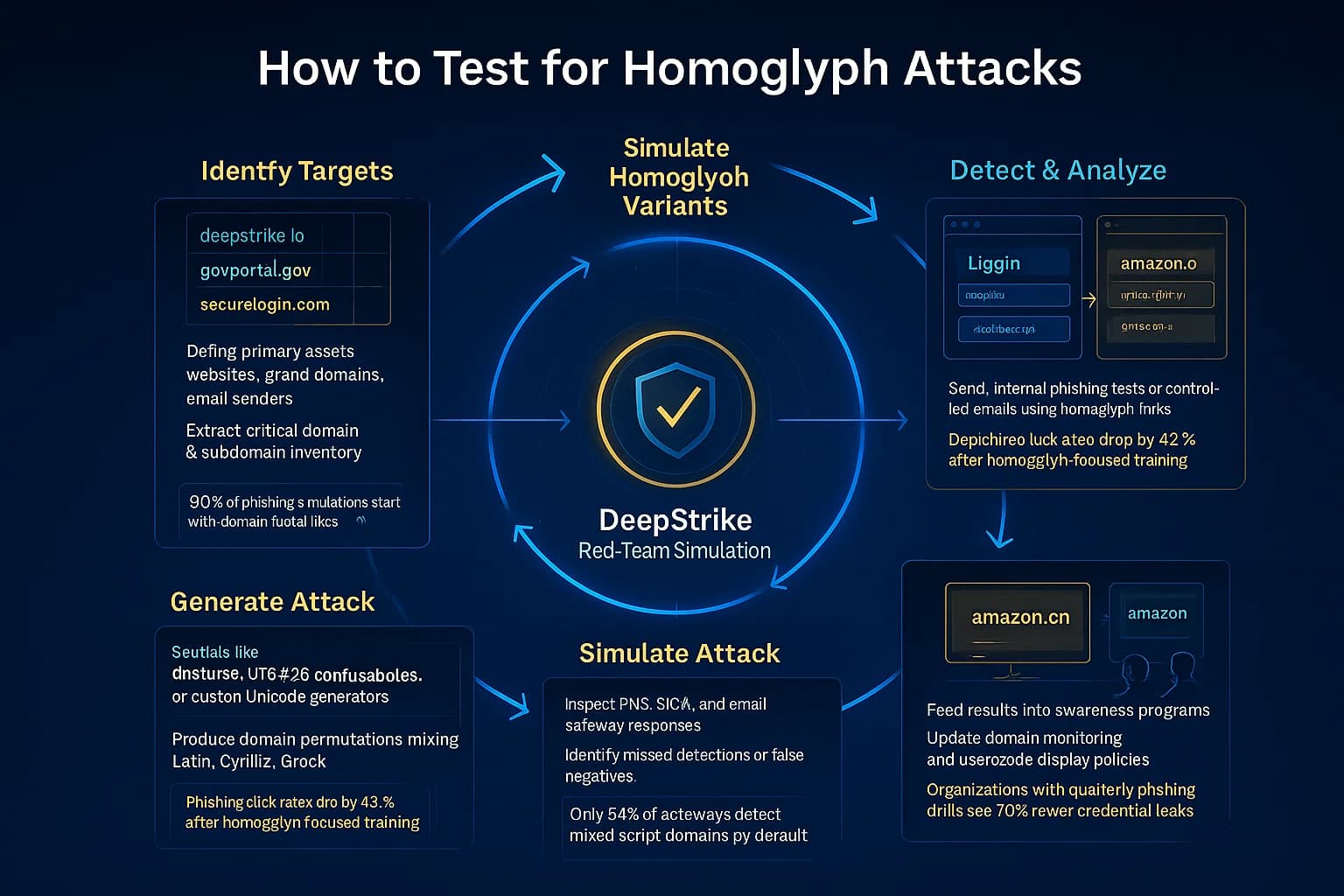

To ensure your organization isn’t vulnerable, include homoglyph scenarios in your security assessments. Here’s a step-by-step approach for testers:

This approach can be integrated into a standard external or red-team test. By simulating real attacker steps, you can validate whether your organization’s email filters, browser settings, and user awareness are effective against homoglyph deception.

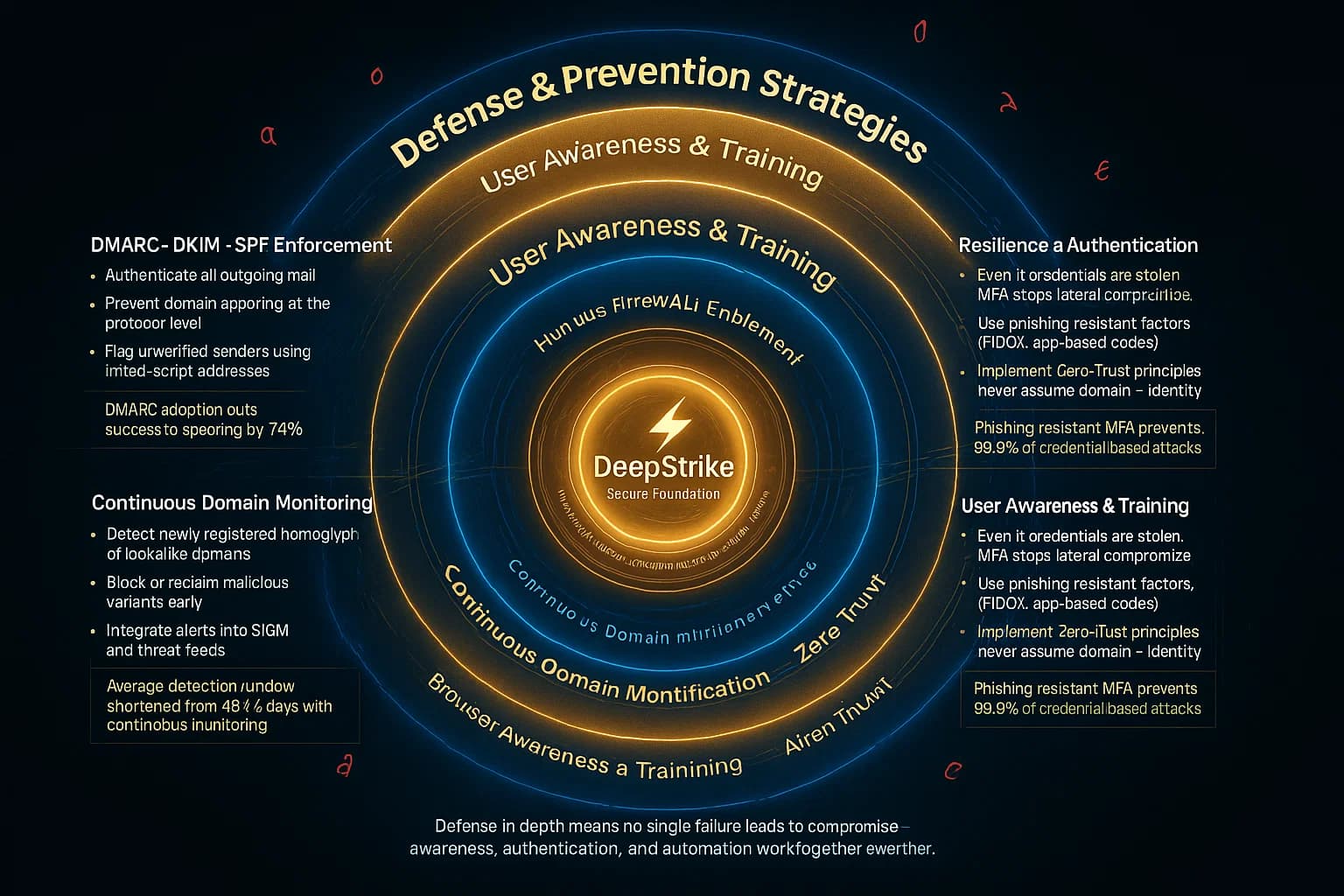

Why this matters: Preventing homoglyph attacks requires both technical and human-focused controls. Below are key best practices:

By combining user vigilance with technical checks e.g. forcing punycode, using spam filters that decode Unicode, and verifying SPF/DKIM, you can greatly reduce homoglyph risks. Remember that even best practices are only effective if regularly reviewed. As attackers invent new tricks, mixed fonts, unconventional scripts, keep your defenses updated. Periodic retesting including re-running homograph generators ensures you stay one step ahead.

Homoglyph (homograph) attacks are a subtle but potent phishing technique. In this article we explained what they are, how they work, real examples of scams, and concrete ways to test and defend against them. The key takeaway is that visibility matters: both users and security systems need to notice when a name isn’t truly what it seems. By including homoglyph scenarios in penetration tests and by implementing controls punycode display, domain monitoring, email auth, MFA, etc., organizations can greatly reduce their risk.

Ready to strengthen your defenses? The evolving threat landscape demands proactive action. If you need to validate your security posture, uncover hidden risks, or improve your resilience, DeepStrike can help.

Our expert team delivers clear, actionable guidance to protect your business from sophisticated attacks. Explore our penetration testing services to see how we can uncover vulnerabilities including homoglyph vectors before attackers do. Drop us a line, we’re always ready to dive in.

About the AuthorMohammed Khalil is a Cybersecurity Architect at DeepStrike, specializing in advanced penetration testing and offensive security operations. With certifications including CISSP, OSCP, and OSWE, he has led numerous red team engagements for Fortune 500 companies, focusing on cloud security, application vulnerabilities, and adversary emulation. His work involves dissecting complex attack chains and developing resilient defense strategies for clients in the finance, healthcare, and technology sectors.

It’s a spoofing attack where a domain, email, or filename is made to look identical to a legitimate one by swapping characters with visually similar glyphs often from another alphabet. For example, using Cyrillic а in place of a Latin a in “example.com” results in a lookalike URL. The user thinks they see the correct name, but in reality it points to a fake resource.

Typosquatting relies on common typing errors like “gooogle.com”, whereas a homoglyph attack actively deceives by using identical-looking characters. Typosquatting only succeeds if the user spells wrong; a homoglyph attack can fool users even if they copy-paste or click a link, because the text appears correct.

Modern browsers Chrome, Firefox, Edge use IDN policies: if a domain has mixed scripts or looks confusable, they often display the punycode form instead of the Unicode string. For example, “аррӏе.com” would appear as “xn--80ak6aa92e.com.” This alerts savvy users. Email systems with advanced filters may also catch known bad domains, but many standard filters do not flag Unicode confusables. Therefore, technical measures help, but user awareness and strict email authentication DMARC/SPF/DKIM are also crucial defenses.

Large brands and financial sites are prime targets. Attackers have mimicked PayPal, banks, cloud services, and popular apps. For instance, phishing campaigns have spoofed Google Drive and DocuSign notifications by inserting Cyrillic letters into names. Streaming and SaaS platforms are also attacked e.g. fake “Spotify” emails. Essentially, any site where users enter credentials can be targeted with a homoglyph-laced fake.

Pen testers can simulate these attacks as part of phishing or red-team assessments. Using tools like dnstwist or custom scripts, testers generate homograph variants of target domains and use them in phishing templates. They then check if employees or security controls notice. Including homoglyph tests in a pentest ensures that any gaps in email filtering or user training are identified and remediated.

Homoglyphs can bypass simple filters because the malicious URL/email looks legitimate at a glance. A filter for “paypal.com” won’t match “pаypal.com” with different characters. Also, if an email is already in a user’s inbox (say, it’s from a trusted provider but with a deceptive address, even SPF/DKIM checks can pass if the domain itself is spoofed. That’s why multi-layered defense authentication, display warnings, MFA and user skepticism are needed alongside technical controls.

Stay secure with DeepStrike penetration testing services. Reach out for a quote or customized technical proposal today

Contact Us